—Guest blog written by Laura Hamilton, Global Readiness Lead at Xbox

Before Europeans cast off for far-flung shores to “discover” the Americas, roughly 60 million Indigenous people already called North, Central, and Southern America, the Caribbean, and the Hawaiian Islands home—and had done so for thousands of years. In fact, members of the Plymouth Colony—founded in 1620 by the English in Massachusetts—would not have survived their first years in North America were it not for the assistance of The Wampanoag (People of the First Light). It’s safe to say that if you reside in one of the previously mentioned locations, you’re on what was traditionally Native land.

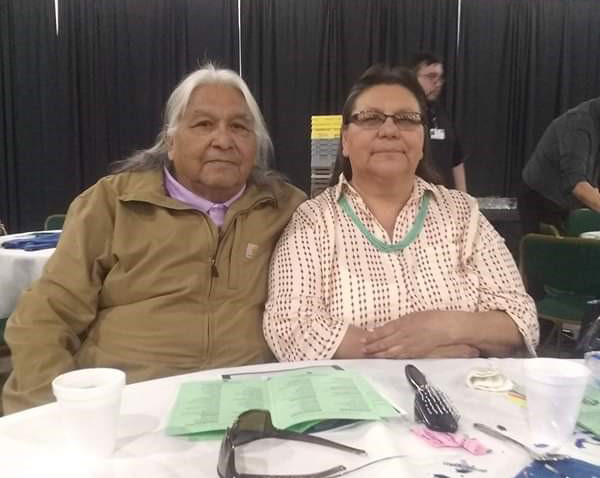

Cedric Good House and his wife Evelyn “Sissy” Good House. Photo courtesy of Cedric and Sissy Good House.

As Native American Heritage Month concludes in the United States, the Age of Empires team and Xbox are honored to feature Hunkpapa elder, Cedric Good House, in our final interview with the cultural consultants who assisted us in rebuilding Age of Empires III: Definitive Edition.

A Knowledge Keeper and member of the Elders’ Preservation Council at Standing Rock (whose charter is to ensure the sacredness of Lakota traditions and safeguard cultural sites for future generations), Mr. Good House’s expertise was critical to our improving the representation of the in-game Lakota civilization. He translated the game dialogue into Lakȟótiyapi (the Lakota language) and generously provided photos of personal items which were used to recreate the details of the Lakota Home City. Cedric uses traditional methods and materials to make regalia, musical instruments, clothing, weapons, and ceremonial items such as carved bison-bone spoons; so, if you’ve visited the updated Lakota Home City, you’ve seen some of the Good House family regalia!

You can read the full interview, below.

♦ ♦ ♦

WORLD’S EDGE: Thank you for being a consultant for World’s Edge, Mr. Good House. We’ve been honored to work with you, and we’d like AoE fans to know a bit about you. First, can you tell us what Hunkpapa means?

CEDRIC GOOD HOUSE: Hunkpapa means “campers at the horn.” Lakota traditionally camp in a semicircle that’s open to the east, and when we gathered every year as the Great Lakota Nation, the Hunkpapa would set up camp at the very tip of the horn, near the opening. So, that’s how the other Lakota bands referenced us: the “Campers at the Horn” or Hunkpapa.

Traditional Lakota hand drum with thunderbird design. Photo courtesy of Cedric Good House.

WORLD’S EDGE: Some of the details in the Lakota Home City are based on personal materials you provided us, such as the Thunderbird drum. Could you talk about its significance?

CEDRIC GOOD HOUSE: Around here [North Dakota], there are certain birds that fly through at the time of storms, and we call them the thunderbirds. Our belief is that when you hear thunder, that’s the birds bringing down the rain, which is where the design on my drum comes from. The thunderbird represents the water that comes from the heavens, and we only use the drum during special ceremonies with certain songs and healings.

WORLD’S EDGE: That is so fascinating. Are you teaching your grandkids how to make drums?

CEDRIC GOOD HOUSE: I will, but maybe in a few more years when they’re more patient. They’re 10 and 11 and are out riding bikes right now! [laughter]

WORLD’S EDGE: One of the more challenging details in the game was the fact that you didn’t historically use flags, so we replaced the flag in the Lakota Home City with an eagle staff. Can you describe what the eagle staff means?

CEDRIC GOOD HOUSE: An eagle staff shows several things: which family the staff represents, whether the family includes warriors wounded in battle, whether the holder has spiritual knowledge, and how large the family unit is.

Randy Good House in a traditional Lakota ceremonial headdress. Photo courtesy of Cedric Good House.

WORLD’S EDGE: You also shared a photograph of your older brother wearing a headdress. Could you tell us about your brother and the meaning of the headdress?

CEDRIC GOOD HOUSE: My brother, Randy, had this amazing musical talent; he could play about seven or eight different instruments. Bright guy with a great mind who was also raising a family. He was twenty when he went into the military during the Vietnam War. We have a big extended family―ten brothers and sisters―and every family group has a Headsman who other family members can look up to. They recognized my brother as our Headsman.

When he came home on leave from Vietnam, we had a big ceremony where we put our family’s warbonnet on him. This was significant because my father was an Episcopal priest, but they still recognized my older brother as being the Headsman in front of the whole tiospeya (extended family). My mom made food for everyone and we had a huge feast to celebrate Randy receiving the warbonnet in front of a couple of hundred people.

The day before he left, my dad took a picture of him with his shirt off because Randy wanted to show that he didn’t have any scars from doing the sacred Sundance, but he still got the warbonnet. There are people who have those scars from the Sundance, but he didn’t need even that to be Headsman.

In December, Randy was back in Vietnam and was wounded in combat on Christmas day. He died on New Year’s Day. We still carry a red feather that signifies being wounded, and the warbonnet is still in our family.

The sacred Black Hills and birthplace of the Lakota people. This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA

WORLD’S EDGE: The Black Hills are included in the game’s storyline. Please explain why they continue to be so critically important to the Lakota.

CEDRIC GOOD HOUSE: If you were to look down on the Black Hills from heaven, you would see they resemble a human heart encircled by a red ring. That red ring was created during a great race between all the nations of humankind and animal kind. The winner would be the last one standing and receive a special gift from God, so all the nations raced and raced for many days, which is where the red ring came from: from the blood of the people and the animals racing around the track.

Now, if you were to stand in the middle of the Black Hills and look straight up, you’d see the Morning Star to the east and a group of stars called chankhahu (Backbone of the Buffalo) that stretches all the way across to the Evening Star in the west. And then the Milky Way (the Holy Road) stretches from north to south. If you look at the whole thing, you have the red circle around the Black Hills and the stars dividing the circle into quadrants. That’s the original medicine wheel. Ĉhaŋgléška: “the circle of life.”

Lakota medicine wheel.

Within each one of these quadrants, our seven sacred ceremonies take place. For example, Bear Butte is in the quadrant where we’d do our fasting and vision quests. Another quadrant is where we greet the thunders and hold that ceremony. In the third section, communal honorings and memorials would be held: such as Making of Relatives (Hunkapi) and a Girl’s Coming of Age (Isnati Awicalowanpi). Farther west is the Great Horned Beast (Devil’s Tower) where White Buffalo Calf Woman gave us the sacred pipe and where we held our very first Sundance. And Wind Cave is where we emerged from the earth, and it’s where my grandmother did her vision quest as a healer who specialized in treating strokes.

Back in the late 1800’s, the U.S. government took the Black Hills and allowed them to be stripped of natural resources (gold, timber, bison, etc.). There’s a lot of U.S. history that must be accepted because we have to move on, but people are ashamed of what happened. They are not going to put it in the news; they’re not ready to take that step. There were ten million Indians here, and now we’re just coming back to a couple of million. The U.S. government gave us many millions for the Black Hills, but we haven’t taken that money because that would literally be purchasing and selling sacred land. That’s why we say we have never sold the Black Hills, and if we have to buy them back, we’ll buy them back. We don’t intend to kick anybody out. All we want is to help people understand our basic concept of mitákuye oyás’iŋ (“we are all related”). We Lakota say that word when we start talking, and we say it when we end our prayers. That’s our word for “amen.” We call it wólakȟota when we’re among ourselves, and that means “peace.” We will be at peace among our relatives because that’s what God told us to do.

WORLD’S EDGE: You’ve also interred family members in the Black Hills for hundreds of years, correct?

CEDRIC GOOD HOUSE: Yes; each Lakota family would have a ceremony for relatives who died, and we buried our relatives in different ways. Typically, we put them up on scaffolding, and there’s a very good reason why: during the great race around the Black Hills between humans and animals, the raven helped us two-legged animals win the race, so we give thanks for that. When our relatives die, we put them up on scaffolding as an offering. In time, they go back to the earth.

All these things are why the Black Hills are so sacred to us.

Moccasins made by Evelyn “Sissy” Good House. Photo courtesy of Cedric Good House.

WORLD’S EDGE: One of the things that people reading this interview might not understand is what it’s like on reservations in the U.S.: how hard it is; what the unemployment is like.

CEDRIC GOOD HOUSE: You learn to be independent. For example, almost every block here in Fort Yates has someone who’s learned to be a mechanic, so if I can’t fix my car, I know somebody who can. Then, someday, they might need my help, so I can return the favor; that’s how we recognize each other’s talents so we can survive.

And the effects of society gets you drinking and drugging, and then that same society tells you that you’re in poverty, so you live in poverty. You live that life.

But you can turn that poverty into good things; that depends on the love for your children and the love for your grandchildren. Every day you hustle in a good way: ensuring that you have food, a warm place, and clean water—warm water—so that everybody can be happy today. The worst thing is from day-to-day; just because you solved a problem today doesn’t mean you’re not going to have it tomorrow. You’re still going to have it tomorrow, but at least today you got it taken care of today.

We’re skilled in survival, and that’s something that we learn when we’re young. So now that our youth communicate among themselves with phones, they’re coordinating and going around putting plastic on windows to help the community get ready for winter….and earning themselves a little money in the process for things they need. So they learn how to take care of themselves. In the meantime, you know, we joke and tease among ourselves so we’re better able to get along. Better able to help each other: because sometimes someone may need $5, but you only have $3, so you help them out with $3. Or they need something we don’t have, but we can give them a loaf of bread or a couple rolls of toilet paper or something—we provide that. So that’s how we’re able to help each other get through the hard times.

The Good House grandchildren in family regalia. Photo courtesy of Cedric and Sissy Good House.

WORLD’S EDGE: What advice would you give to other media companies that want to portray Lakota culture, history, individuals, and current tribal efforts?

CEDRIC GOOD HOUSE: The most important word of advice I’d give is to take the time to consult with members of the tribal nation who are known for their knowledge.

WORLD’S EDGE: When you look to the future, what are your hopes and goals for future generations of Lakota?

CEDRIC GOOD HOUSE: What I’m doing today, I do for my grandkids and those who they influence. I’m influencing them in a way that I hope they’ll be able to repeat to influence their peers (and their own children and grandchildren). I teach my grandchildren, but I’m also teaching the seven generations to come. So, my teaching has to be in a way that my grandchildren can learn and be able to carry and teach their children, who will teach their children, so that my teaching will go to seven generations—the same way that I’ve been taught by people seven generations before me. Our influence has to be that strong.

♦ ♦ ♦

Today, Cedric and his wife Sissy (who’s been honored for her teaching work in local schools) continue to speak, sing, and teach Lakȟótiyapi to their grandchildren and their local community.