—Guest blog written by Kat Fritz (2021) and edited by Grace Rojas

February 1st marks the beginning of Black History Month in the United States. In honor of this month, we will be sharing stories of Black individuals who contributed to the formation of the United States. You may be familiar with some of the figures we have highlighted or maybe this is your first time learning about them and their contributions; either way, our team would like to encourage you to read and share their stories. In addition, to aid your educational journey on Black History Month you can visit blackhistorymonth.gov .

♦ ♦ ♦

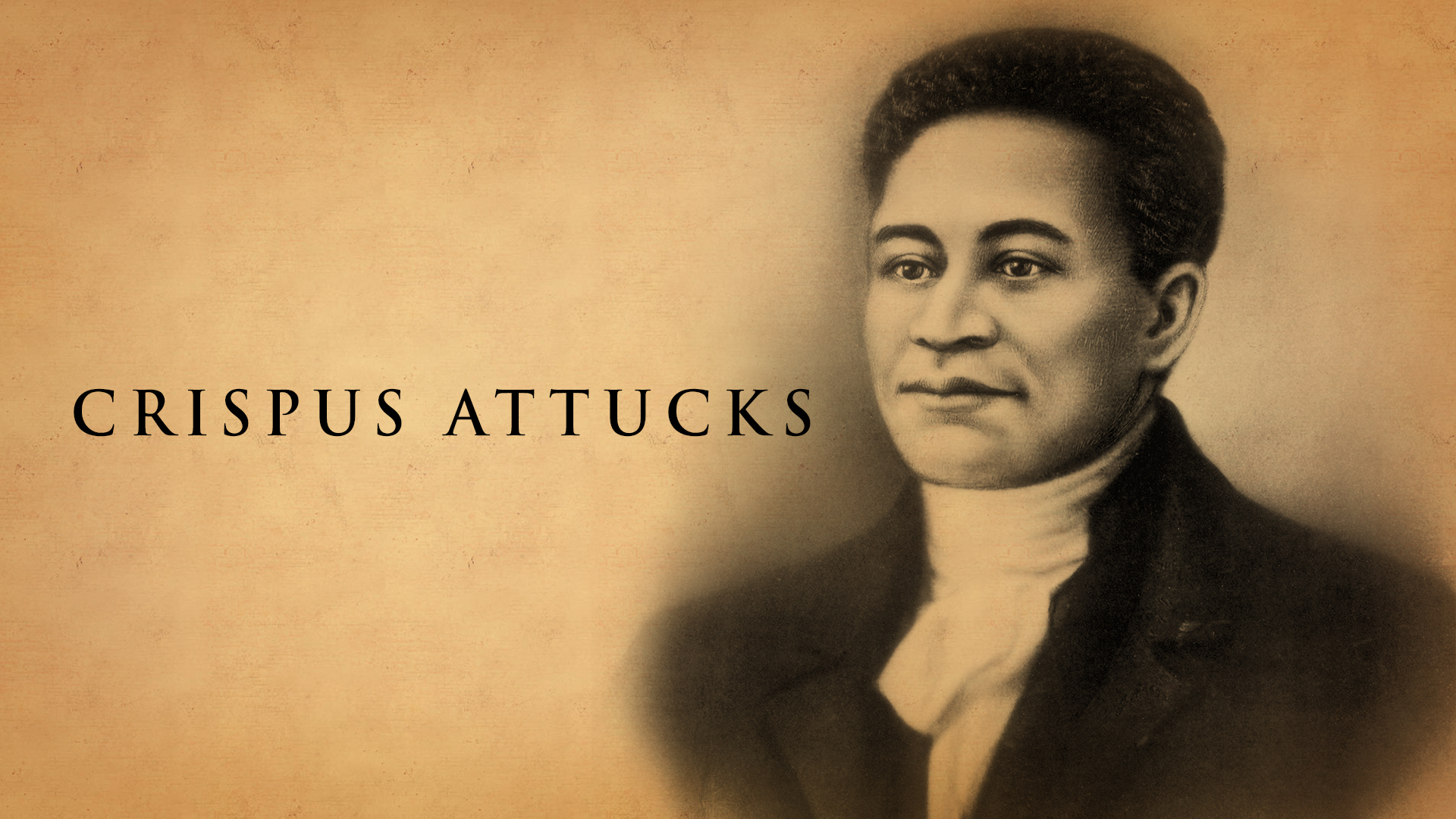

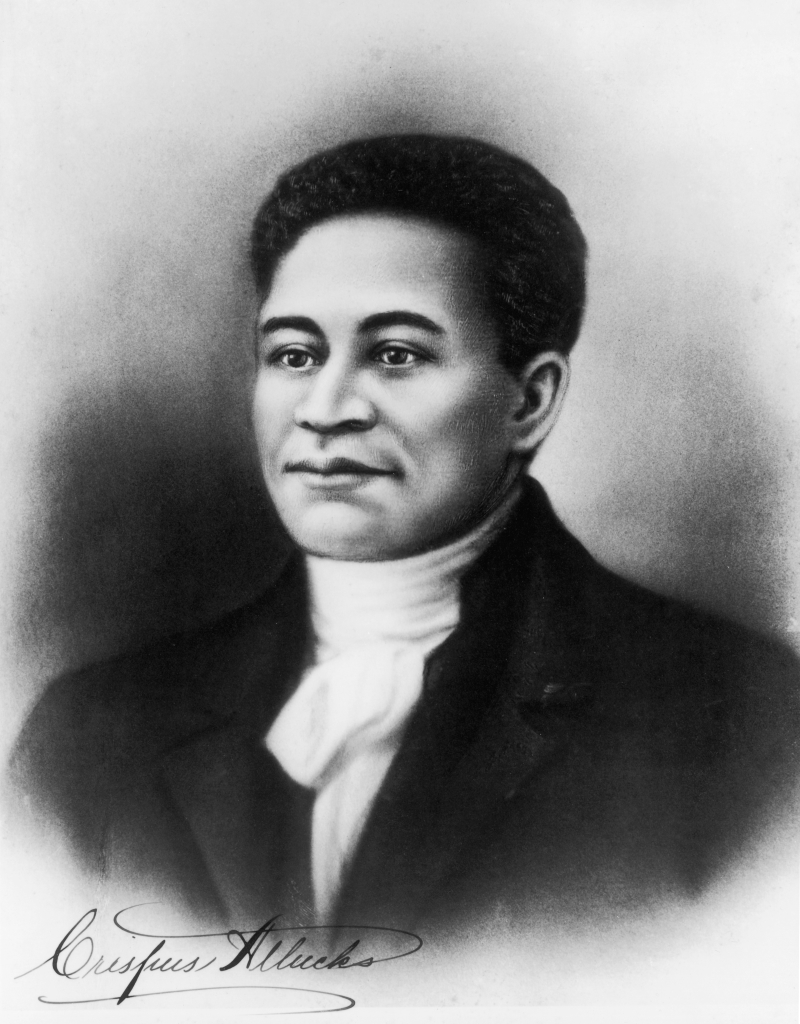

Crispus Attucks (c. 1723 – 1770)

Crispus Attucks was born into slavery during the eighteenth century. His mother was Nancy Attucks—a Natick Indian—and his father was believed to be an enslaved man named Prince Yonger. On March 5, 1770, Attucks rioted alongside other colonists in front of a customs house. The tension between the British soldiers and the civilians intensified, and the soldiers fired guns into the crowd. Attucks and four others were killed, and six more were injured in what would come to be known as the Boston Massacre: actions that would ignite the colonists’ hunger for American independence.

There is little information on Attucks’ life or family, but historians believe that he grew up in a town outside of Boston. Attucks ardently desired freedom, so he attempted to escape the bonds of slavery despite the consequences of the time. In 1750, a newspaper advertisement in the Boston Gazette offered 10 British pounds (plus expenses) for returning Crispus to his enslaver. Fortunately, the escape was successful: securing his freedom from the institution of slavery for the rest of his life. He became a mariner—one of the few occupations accessible to a non-white person. When he was not at sea on trading ships or whaling vessels, he found work as a ropemaker.

Like many other mariners, Crispus Attucks felt threatened by British rule. British soldiers and sailors often took part-time jobs from locals during their off-duty time: stealing positions from the local labor force. There was also the looming threat that Attucks could be forcibly drafted into the Royal Navy by British press gangs: roaming bands of soldiers who would capture men and boys, trapping them onboard military ships. With the British depressing wages and increasing taxes, tensions between colonists and the British were soaring, and bloodshed appeared inevitable.

On March 5, 1770, a British soldier entered a pub looking for work, but Crispus Attucks and other sailors responded with shouts and jeers. The events of that evening are a source of debate, but it is believed that a group of Bostonians started taunting a redcoat near Boston’s Old State House—one of the oldest structures in the United States and Boston’s oldest surviving public building.

Soldiers from the 29th Regiment of Foot came to their fellow soldier’s defense as the situation escalated. Attucks and other colonists struck the soldiers with clubs and sticks. There is no clear consensus on what happened next, but someone reportedly said, “Fire,” and a Redcoat shot into the crowd. Once the first shot rang out into the night, other British soldiers began firing. Attucks was shot twice in the chest, with the second shot proving fatal. Many accounts state that he was the first victim of the Boston Massacre.

Growing tensions in Boston led to the Boston Massacre of 1770.

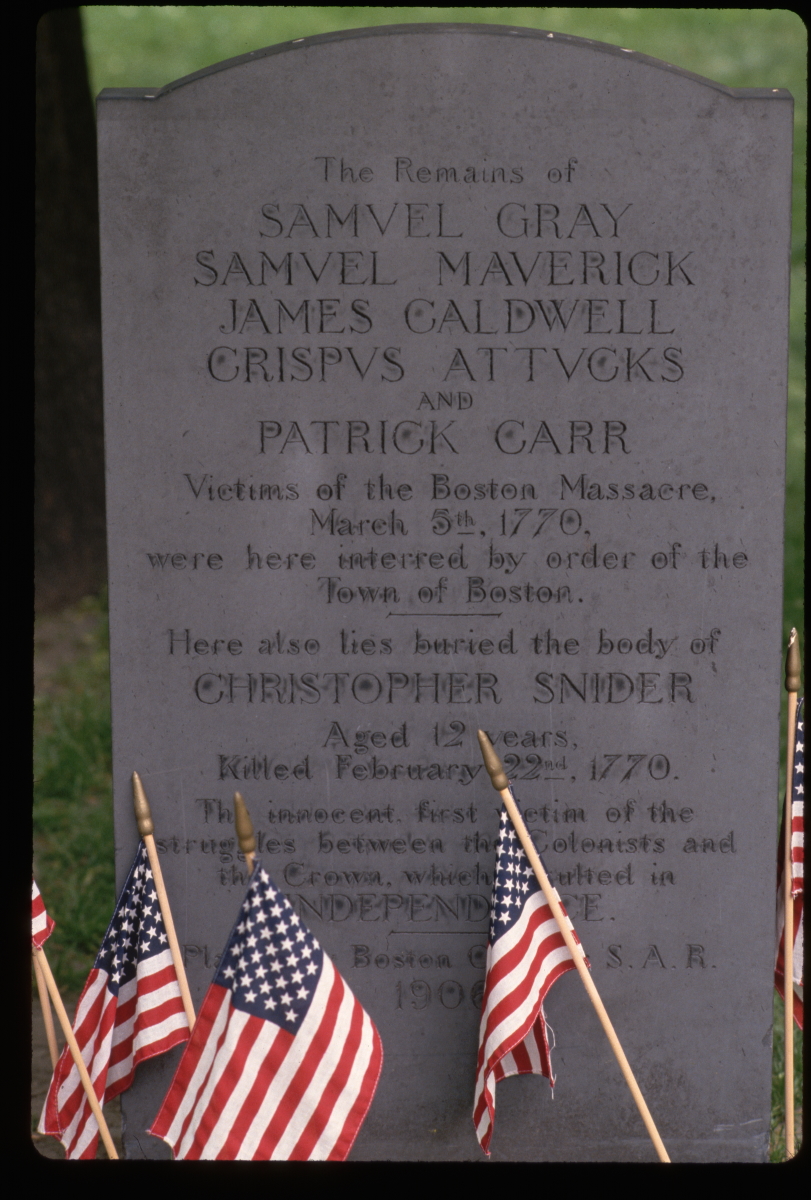

The deaths of Attucks and the four other men unified the colonies against British rule, marking a turning point in United States history. Attucks became a martyr of liberty, paving the way for the American Revolution. Samuel Adams—a Founding Father of the United States—organized a procession to carry the caskets of Crispus Attucks and the other victims of the massacre (James Caldwell, Patrick Carr, Samuel Gray, and Samuel Maverick) to Boston’s Faneuil Hall to lay in state for three days before their public funeral. It is estimated that 12,000 people—about half of Boston’s population at the time—joined the procession to the graveyard.

However, statements and depictions of the massacre reveal a great deal about the realities of the time. John Adams—who would later become the second president of the United States—defended the soldiers, vilifying Crispus Attucks as the aggressive instigator of the crowd. Adams argued that Attucks’ race, height, and musculature justified the fear of the Redcoats.

Historical views of Attucks are present in the four engravings of the Boston Massacre that circulated in 1770. The engravings served as colonial propaganda by illustrating the soldiers as an organized line against a defenseless crowd. The first was by Henry Pelham, who was neither credited nor paid for his work. Paul Revere—a patriot famous for warning Colonial troops of a British attack—copied Pelham’s illustration almost exactly and brought it to press days before Pelham did. Another man, Jonathan Mulliken, released his own version based on Revere’s.

Crispus Attucks

Though the engravings differed slightly, all the engravings had one detail in common: Crispus Attucks was illustrated without African American or Indigenous American features. A lithograph from J.H. Bufford’s Lithography Co. based on an illustration by W.L. Champney (1856) provided a new rendering of the event with Attucks as the central figure of the Boston Massacre. Most notably, it is also the first depiction of Crispus Attucks as a person of color. Additionally, despite the Boston Massacre’s influence on the American Revolution, Attucks is never mentioned in David Ramsay’s The History of the American Revolution (1789)—the first published account of the Revolution.

In 1851, to contest the ambiguity shrouding Attucks, seven Bostonians petitioned to erect a monument of Attucks to honor his role as the first causality of the American Revolution. One of the petitioners was William Cooper Nell: an African American abolitionist, historian, and author of The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution. In the book, Nell describes how their petition was denied while the monument of Isaac Davis was granted, noting that the difference between the two men was that Isaac Davis had been a White advocate of the American Revolution.

A gravestone commemorating the victims of the Boston Massacre – Granary Burial Ground, Boston, Massachusetts

Fortunately, thanks to the support of abolitionists, the Boston Massacre/Crispus Attucks monument was erected in 1888. The monument includes an illustration of the Boston Massacre where Attucks has African American and Indigenous American features.

Crispus Attucks became a symbol for abolitionism and the Civil Rights Movement, for he was a patriot who died rioting against oppressors. In Why We Can’t Wait (1964), Martin Luther King, Jr. noted that—despite Black erasure in history books—Black children knew Attucks was the first person to shed blood for their country in the revolution that freed the United States from its British oppressors. Attucks’ role in US history demonstrates a clear link between patriotism, freedom, and racial inequality.

The Black Revolutionary War Patriots Commemorative Silver Dollar featuring an illustration of Attucks; The Crispus Attucks Park in Washington, D.C.; the Attucks Theatre; and other tributes keep his contributions to the United States alive. Thanks to the efforts of abolitionists and Black activists, Crispus Attucks still lives on in memory for his remarkable role in American Independence.

♦ ♦ ♦

We encourage you to read, learn and visit africanamericanhistorymonth.gov for more information about African American heroes and leaders in American history.